-40%

1975 Yamaha RD350B - 7-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test Article

$ 7.3

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1975 Yamaha RD350B - 7-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test ArticleOriginal, vintage magazine article.

Page Size: Approx. 8" x 11" (21 cm x 28 cm) each page

Condition: Good

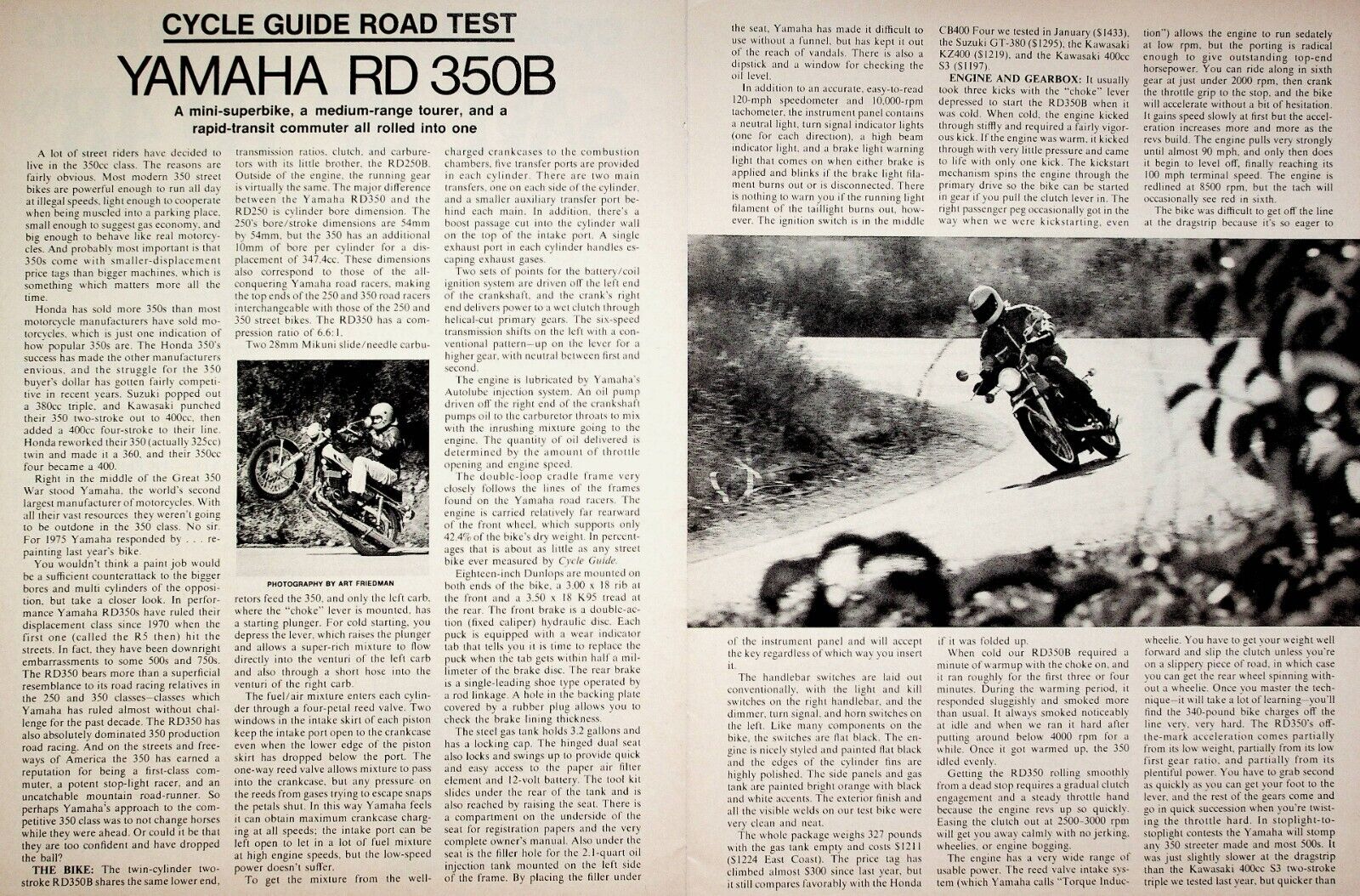

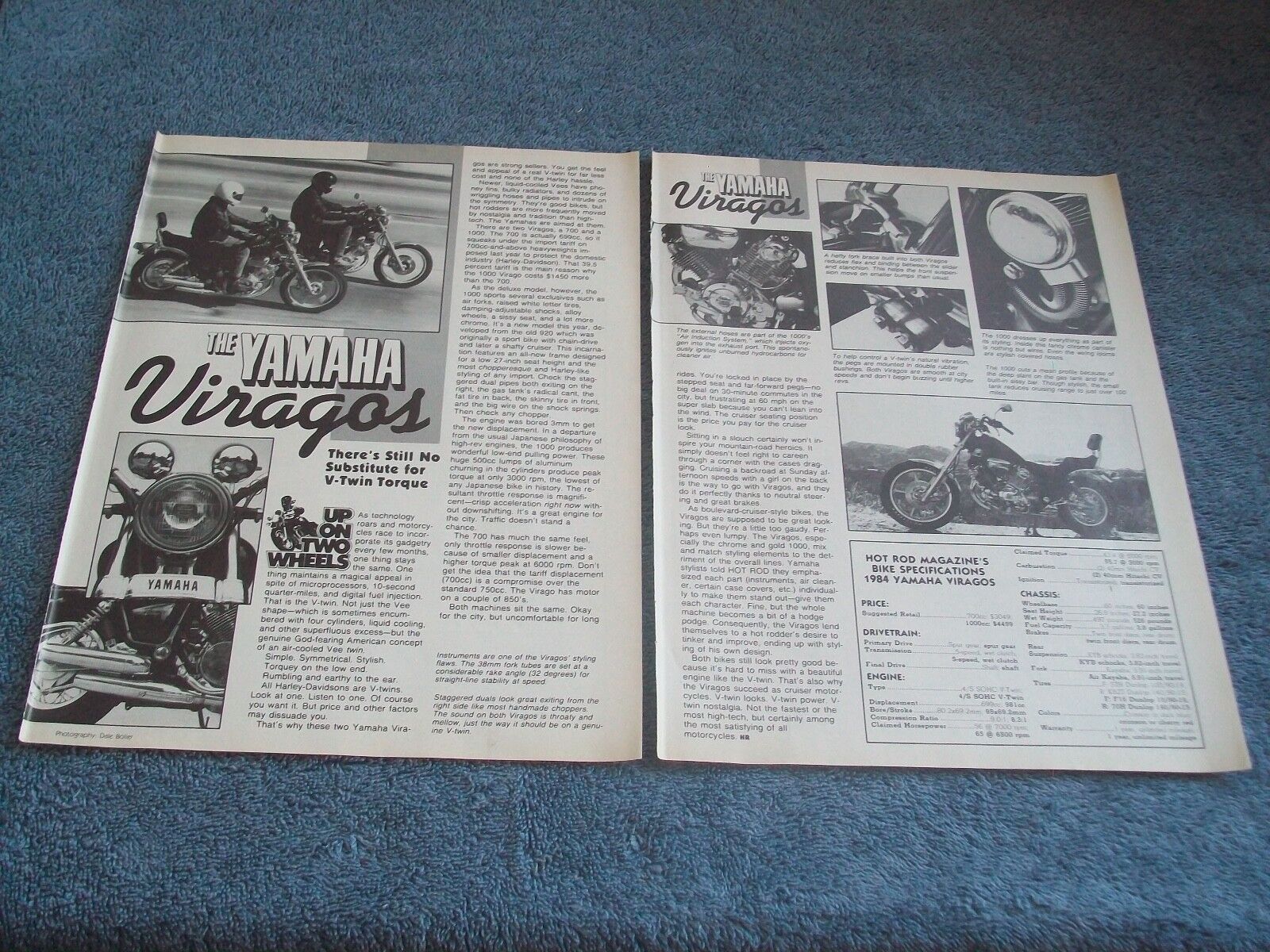

CYCLE GUIDE ROAD TEST

YAMAHA RD 350B

A mini-superbike, a medium-range tourer, and a

rapid-transit commuter ail rolled into one

A lot of street riders have decided to

live in the 350cc class. The reasons arc

fairly obvious. Most modern 350 street

bikes are powerful enough io run all day

at illegal speeds, light enough to cooperate

when being muscled into a parking place,

small enough to suggest gas economy, and

big enough to behave like real motorcy-

cles. And probably most important is that

350s come with smaller-displacement

price tags than bigger machines, which is

something which matters more all the

time.

Honda has sold more 350s than most

motorcycle manufacturers have sold mo-

torcycles, which is just one indication of

how popular 350s are. The Honda 350's

success has made the other manufacturers

envious, and the struggle for the 350

buyer's dollar has gotten fairly competi-

tive in recent years. Suzuki popped out

a 380cc triple, and Kawasaki punched

their 350 two-stroke out to 400cc. then

added a 400cc four-stroke to their line.

Honda reworked their 350 (actually 325cc)

twin and made it a 360. and their 350cc

four became a 400.

Right in the middle of the Great 350

War stood Yamaha, the world's second

largest manufacturer of motorcycles. With

all their vast resources they weren’t going

to be outdone in the 350 class. No sir.

For 1975 Yamaha responded by . . . re-

painting last year’s bike.

You wouldn’t think a paint job would

be a sufficient counterattack to the bigger

bores and multi cylinders of the opposi-

tion. but take a closer look. In perfor-

mance Yamaha RD350s have ruled their

displacement class since 1970 when the

first one (called the R5 then) hit the

streets. In fact, they have been downright

embarrassments to some 500s and 750s.

The RD350 bears more than a superficial

resemblance to its road racing relatives in

the 250 and 350 classes—classes which

Yamaha has ruled almost without chal-

lenge for the past decade. The RD350 has

also absolutely dominated 350 production

road racing. And on the streets and free-

ways of America the 350 has earned a

reputation for being a first-class com-

muter. a potent stop-light racer, and an

uncatchable mountain road-runner. So

perhaps Yamaha’s approach to the com-

petitive 350 class was to not change horses

while they were ahead. Or could it be that

they are too confident and have dropped

the ball?

THE BIKE: The twin-cylinder two-

stroke RD35OB shares the same lower end,

transmission ratios, clutch, and carbure-

tors with its little brother, the RD250B.

Outside of the engine, the running gear

is virtually the same. The major difference

between the Yamaha RD350 and the

RD250 is cylinder bore dimension. The

250's bore/stroke dimensions are 54mm

by 54mm. but the 350 has an additional

10mm of bore per cylinder for a dis-

placement of 347.4cc. These dimensions

also correspond to those of the all-

conquering Yamaha road racers, making

the top ends of the 250 and 350 road racers

interchangeable with those of the 250 and

350 street bikes. The RD350 has a com-

pression ratio of 6.6:1.

Two 28mm Mikuni slide/needle carbu-

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ART FRIEDMAN

retors feed the 350, and only the left carb,

where the “choke” lever is mounted, has

a starting plunger. For cold starting, you

depress the lever, which raises the plunger

and allows a super-rich mixture to flow

directly into the venturi of the left carb

and also through a short hose into the

venturi of the right carb.

The fuel/air mixture enters each cylin-

der through a four-petal reed valve. Two

windows in the intake skirt of each piston

keep the intake port open to the crankcase

even when the lower edge of the piston

skirl has dropped below the port. The

one-way reed valve allows mixture to pass

into the crankcase, but any pressure on

the reeds from gases trying to escape snaps

the petals shut. In this way Yamaha feels

it can obtain maximum crankcase charg-

ing al all speeds; the intake port can be

left open to let in a lot of fuel mixture

at high engine speeds, but the low-speed

power doesn’t suffer.

To gel the mixture from the well-

charged crankcases to the combustion

chambers, five transfer ports are provided

in each cylinder. There are two main

transfers, one on each side of the cylinder,

and a smaller auxiliary transfer port be-

hind each main. In addition, there's a

boost passage cut into the cylinder wall

on the lop of the intake port. A single

exhaust port in each cylinder handles es-

caping exhaust gases.

Two sets of points for the batlery/coil

ignition system are driven off the left end

of the crankshaft, and the crank’s right

end delivers power to a wet clutch through

helical-cut primary gears. The six-speed

transmission shifts on the left with a con-

ventional pattern —up on the lever for a

higher gear, with neutral between first and

second.

The engine is lubricated by Yamaha's

Autolube injection system. An oil pump

driven oil the right end of the crankshaft

pumps oil to the carburetor throats to mix

with the inrushing mixture going to the

engine. The quantity of oil delivered is

determined by the amount of throttle

opening and engine speed.

The double-loop cradle frame very

closely follows the lines of the frames

found on the Yamaha road racers. The

engine is carried relatively far rearward

of the front wheel, which supports only

42.4% of the bike’s dry weight. In percent-

ages that is about as little as any street

bike ever measured by Cycle Guide.

Eighteen-inch Dunlops are mounted on

both ends of the bike, a 3.00 x 18 rib at

the front and a 3.50 x 18 K95 tread at

the rear. The front brake is a double-ac-

tion (fixed caliper) hydraulic disc. Each

puck is equipped with a wear indicator

lab that tells you it is lime to replace the

puck when the tab gels within half a mil-

limeter of the brake disc. The rear brake

is a single-leading shoe type operated by

a rod linkage. A hole in the backing plate

covered by a rubber plug allows you to

check the brake lining thickness.

The steel gas tank holds 3.2 gallons and

has a locking cap. The hinged dual seat

also locks and swings up to provide quick

and easy access to the paper air filler

element and 12-volt battery. The tool kit

slides under the rear of the tank and is

also reached by raising the seat. There is

a compartment on the underside of the

seat for registration papers and the very

complete owner’s manual. Also under the

seal is the filler hole for the 2.1-quart oil

injection lank mounted on the left side

of the frame. By placing the filler under

the seat. Yamaha has made it difficult to

use without a funnel, but has kept it out

of the reach of vandals. There is also a

dipstick and a window for checking the

oil level.

In addition to an accurate, easy-lo-read

120-mph speedometer and 10.000-rpm

tachometer, the instrument panel contains

a neutral light, turn signal indicator lights

(one for each direction), a high beam

indicator light, and a brake light warning

light that comes on when either brake is

applied and blinks if the brake light fila-

ment burns out or is disconnected. There

is nothing to warn you if the running light

filament of the taillight burns out. how-

ever. The ignition switch is in the middle

of the instrument panel and will accept

the key regardless of which way you insert

it.

The handlebar switches are laid out

conventionally, with the light and kill

switches on the right handlebar, and the

dimmer, turn signal, and horn switches on

the left. Like many components on the

bike., the switches are flat black. The en-

gine is nicely styled and painted fiat black

and the edges of the cylinder fins are

highly polished. The side panels and gas

tank are painted bright orange with black

and while accents. The exterior finish and

all the visible welds on our lest bike were

very clean and neat.

The whole package weighs 327 pounds

with the gas tank empty and costs SI211

(24 East Coast). The price tag has

climbed almost 0 since last year, but

it still compares favorably with the Honda

CB400 Four we tested in January (33).

the Suzuki GT-380 (95), the Kawasaki

KZ400 (19). and the Kawasaki 400cc

S3 (SI 197).

ENGINE AND GEARBOX: It usually

look three kicks with the “choke” lever

depressed to start the RD35OB when it

was cold. When cold, the engine kicked

through stiffly and required a fairly vigor-

ous kick. If the engine was warm, it kicked

through with very little pressure and came

to life with only one kick. The kickstart

mechanism spins the engine through the

primary drive so the bike can be started

in gear if you puli the clutch lever in. The

right passenger peg occasionally got in the

way when we were kickstarting, even

if it was folded up.

When cold our RD350B required a

minute of warmup with the choke on. and

it ran roughly for the first three or four

minutes. During the wanning period, it

responded sluggishly and smoked more

than usual. It always smoked noticeably

al idle and when we ran it hard after

putting around below 4000 rpm for a

while. Once it got warmed up. the 350

idled evenly.

Getting the RD35O rolling smoothly

from a dead stop requires a gradual clutch

engagement and a steady throttle hand

because the engine revs up so quickly.

Easing the clutch out at 2500-3000 rpm

will get you away calmly with no jerking,

wheelies, or engine bogging.

The engine has a very wide range of

usable power. The reed valve intake sys-

tem (which Yamaha calls “Torque Indue-

lion”) allows the engine to run sedately

al low rpm, but the porting is radical

enough to give outstanding top-end

horsepower. You can ride along in sixth

gear at just under 2000 rpm. then crank

the throttle grip to the stop, and the bike

will accelerate without a bit of hesitation.

It gains speed slowly at first but the accel-

eration increases more and more as the

revs build. The engine pulls very strongly

until almost 90 mph. and only then does

it begin to level off. finally reaching its

100 mph terminal speed. The engine is

redlined at 8500 rpm. but the tach will

occasionally see red in sixth.

The bike was difficult to get off the line

at the dragstrip because it’s so eager to

wheelie. You have to get your weight well

forward and slip the clutch unless you're

on a slippery piece of road, in which case

you can get the rear wheel spinning with-

out a wheelie. Once you master the tech-

nique—it will take a lot of learning—you'll

find the 340-pound bike charges oft' the

line very, very hard. The RD35O's off-

the-mark acceleration comes partially

from its low weight, partially from its low

first gear ratio, and partially from its

plentiful power. You have to grab second

as quickly as vou can get your foot to the

lever, and the rest of the gears come and

go in quick succession when you're twist-

ing the throttle hard. In stoplight-to-

stoplighl contests the Yamaha will stomp

any 350 Streeter made and most 500s. It

was just slightly slower at the dragstrip

than the Kawasaki 400cc S3 two-stroke

triple we tested last year, but quicker than...

15945